FERNANDO BENGOECHEA 1965 - 2004

A massive Tsunami took the life of internationally acclaimed photographer Fernando Bengoechea in December 2004. He was vacationing in Sri Lanka with partner Nate Berkus. Nate miraculously survived the disaster. Fernando's body was never found. He was 39.

You can learn a little more about it from this Oprah Winfrey show.

We are so incredibly touched by the way Nate Berkus describes Fernando, their love and how he changed his life for the better in his book The Things That Matter. In the book, Nate also shares the incredible Tsunami survival experience. Here is the excerpt of this amazing read.

"Fernando and I met in 2003 at a photo shoot for O at Home magazine. He had been hired to photograph the makeover process of a living room I was brought in to redo. How many people are lucky enough to have the very first meeting of a great love documented by the nature of what they do professionally? The day I met him, I could see, through his photographs, how he saw me, and I remember thinking, Things don't get any better than this.

Fernando was audacious and complicated and spontaneous and sophisticated and charismatic and demanding and graceful and volatile and extravagant and occasionally impossible. And when he walked into the room, he pretty much owned it. He was also contemplative and nurturing and soulful and insightful and intuitive and deeply kind. Our attraction was instantaneous and it was powerful. One week after we began dating, Fernando flew to Chicago to visit me. When he walked into the apartment, I naturally assumed he would be bowled over by its scale and design, and he was . . . only not quite in the way I imagined. In his typically contrarian style, Fernando said, "You are a more interesting person than this. I'm surprised that you live someplace so traditional."

Fernando always woke up earlier than I did. And after that first night in my apartment, I walked into the living room to find that while I was sleeping, he had rearranged all the furniture. A lot of people would have been hurt or insulted or a bit of both. But I wasn't bothered in the least. I actually kind of loved that he'd done that. I loved that as a photographer he was so visual that he couldn't bear to look at something he thought could be improved upon. One reason Fernando was a genius at photographing interiors is that he was just compelled to experiment with spaces, to design new rooms and create tableaux that didn't exist. It became a thing with us. We played with our stuff the way some couples do the Sunday Times crossword puzzle. I would visit him in New York on the weekends, and we'd spend hours moving his living room around. Though I didn't put it together at the time, we would do the exact same things—reshuffle furniture; swap a picture for a mirror; rearrange books, and surfaces, and closets; add some texture; subtract some pillows, try this higher, that lower—I did in my bedroom as a child. We became partners in the pursuit of creating a feeling of home. It was a feeling I had never had so strongly before.

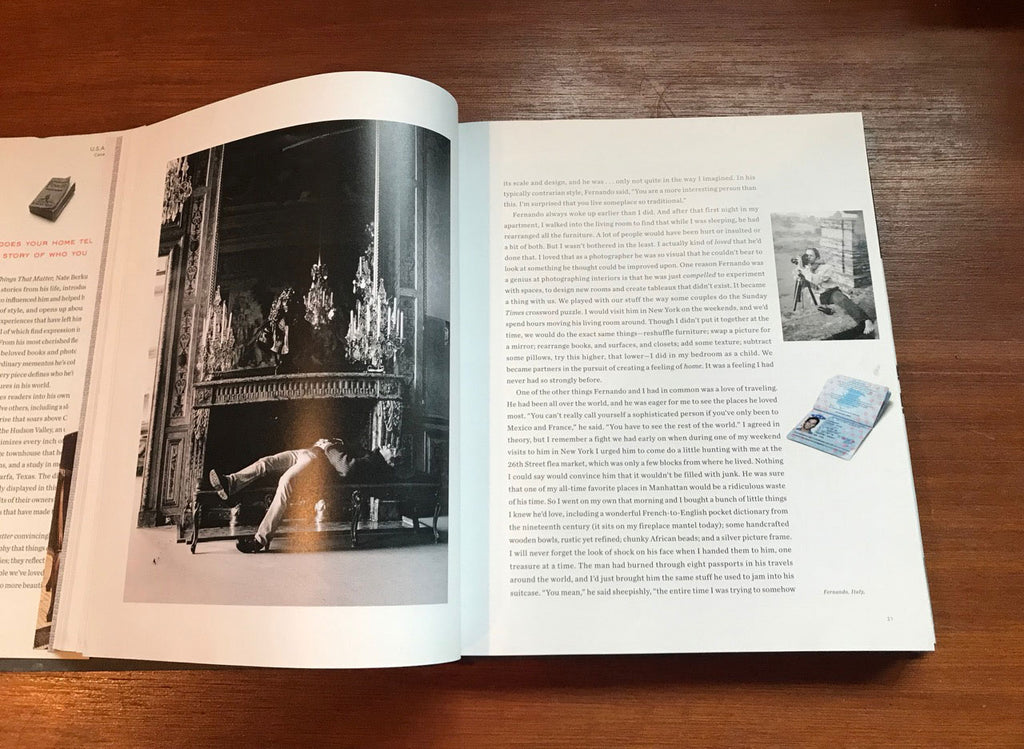

One of the other things Fernando and I had in common was a love of traveling. He had been all over the world, and he was eager for me to see the places he loved most. "You can't really call yourself a sophisticated person if you've only been to Mexico and France," he said. "You have to see the rest of the world." I agreed in theory, but I remember a fight we had early on when during one of my weekend visits to him in New York I urged him to come do a little hunting with me at the 26th Street flea market, which was only a few blocks from where he lived. Nothing I could say would convince him that it wouldn't be filled with junk. He was sure that one of my all-time favorite places in Manhattan would be a ridiculous waste of his time. So I went on my own that morning and I bought a bunch of little things I knew he'd love, including a wonderful French-to-English pocket dictionary from the nineteenth century (it sits on my fireplace mantel today); some handcrafted wooden bowls, rustic yet refined; chunky African beads; and a silver picture frame. I will never forget the look of shock on his face when I handed them to him, one treasure at a time. The man had burned through eight passports in his travels around the world, and I'd just brought him the same stuff he used to jam into his suitcase. "You mean," he said sheepishly, "the entire time I was trying to somehow fit all these things between my knees on a crowded airplane, they've been sitting on card tables four blocks from my apartment?"

Fernando had taste, much more layered than my own. When I walked into his loft for the first time, I knew in my gut we would end up together. For starters, the place was ridiculously clean. It was bright and light and filled with vintage objects he'd dragged home from Russia and Vietnam, Italy and Thailand, Patagonia and the Basque Country, and a hundred other exotic places from his life on the road. In addition to his sofa on the other side of the room, he had a mattress on the floor in front of the fireplace, draped with a mix of plush, hand-knit blankets in shades of ivory and ecru, across from a wall of books he'd collected from museums and bookshops all over the world. Everywhere my eye landed, I saw something I loved. Each piece had a story to tell. His glazed pottery was from a small village in China; his incense from Esteban in Paris; his pots and pans from South America, so fine they almost made me want to cook (I said almost); two floor-to-ceiling shelves were filled with embroidered textiles from Morocco and Mexico and India. The things in his apartment and the stories that went with them opened my eyes to cultures I only dimly knew existed. He made me want to watch the sun come up over the Sea of Galilee and study the tile mosaics of Marrakesh and buy saffron and curry at the Malaysian bazaars. He showed me a bigger life than I'd ever dreamed of for myself.

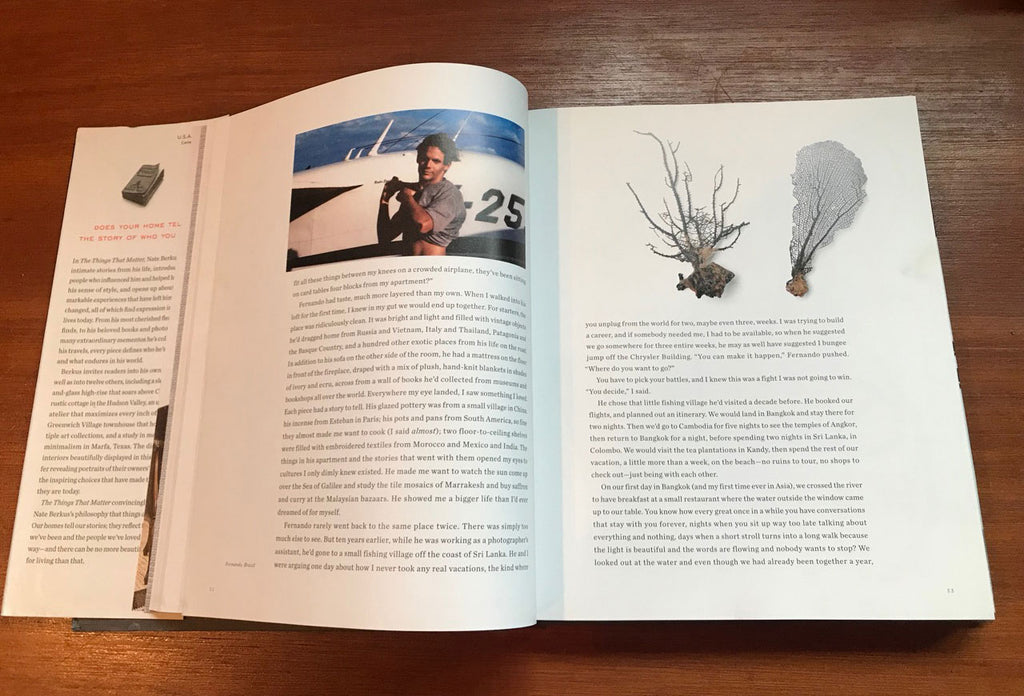

Fernando rarely went back to the same place twice. There was simply too much else to see. But ten years earlier, while he was working as a photographer's assistant, he'd gone to a small fishing village off the coast of Sri Lanka. He and I were arguing one day about how I never took any real vacations, the kind where you unplug from the world for two, maybe even three, weeks. I was trying to build a career, and if somebody needed me, I had to be available, so when he suggested we go somewhere for three entire weeks, he may as well have suggested I bungee jump off the Chrysler Building. "You can make it happen," Fernando pushed. "Where do you want to go?" You have to pick your battles, and I knew this was a fight I was not going to win. "You decide," I said.

He chose that little fishing village he'd visited a decade before. He booked our flights, and planned out an itinerary. We would land in Bangkok and stay there for two nights. Then we'd go to Cambodia for five nights to see the temples of Angkor, then return to Bangkok for a night, before spending two nights in Sri Lanka, in Colombo. We would visit the tea plantations in Kandy, then spend the rest of our vacation, a little more than a week, on the beach—no ruins to tour, no shops to check out—just being with each other.

On our first day in Bangkok (and my first time ever in Asia), we crossed the river to have breakfast at a small restaurant where the water outside the window came up to our table. You know how every great once in a while you have conversations that stay with you forever, nights when you sit up way too late talking about everything and nothing, days when a short stroll turns into a long walk because the light is beautiful and the words are flowing and nobody wants to stop? We looked out at the water and even though we had already been together a year, that day we talked, really talked, about how we had both come to this place in our lives, where we knew we were finally exactly where we were meant to be, with exactly the person we were meant to be with. Fernando was born in Argentina, the youngest of three brothers. He hadn't had an easy time with his father, and later on he'd been in a number of complicated relationships. Parts of his past clearly made him uncomfortable. On the ferry back to our hotel, he seemed to shut down, becoming distant and quiet. "What's wrong?" I asked. He was worried that he'd revealed too much to me. He was normally so confident that it was odd to see him embarrassed. The sun was out, and the sky looked like a pearl, and we sat there on the boat for a few minutes, just feeling it rock and skim across the river. "Look," I said, taking him in my arms, "wherever you have been, whatever you have done in your life, it doesn't matter. We're together now."

Our trip was full of wonder and fun and—though I didn't sense it at the time—peculiar little moments of risk. That year-2004—was the first Cambodia opened up to tourists, and when we visited the temples of Angkor, you had to make certain you stayed on the path for fear of old, buried land mines. In Siam Reap, we checked into a beautiful old hotel and set off exploring the antiques markets. At one of the temples, I remember, there was a snake in a cage with a fence around it. Two tourists were there, staring silently at the snake, and Fernando snuck up behind the man—a perfect stranger—and grabbed his ankle. The man's girlfriend doubled over with laughter, and eventually the man did, too. It takes nerve, and a huge sense of humor, to approach a stranger that way—Fernando had both.

In Colombo, our charmingly shabby hotel failed to charm Fernando, and the city was congested and smoggy, to boot. Fernando was unhappy. "I shouldn't have brought you here," he said. I told him I was fine just being with him, and pretty soon his mood lifted enough that he decided we should leave the city a little earlier than planned and drive to the beach. The water was why we had traveled all this way, right? As we drove, we passed by two different orphanages, the children playing outside in the sun. Christmas was only a few days away, and I felt that I should stop the car and try to do something for them, but I just didn't have the courage. I guess I was afraid of being perceived as the American who shows up unannounced and invades their space. I am still haunted by my mistake.

The Stardust Beach Hotel was owned by a Danish couple, Per and Merete, who had lived and worked in this tiny community for years. For breakfast every day, Per would bring bread fresh from the oven. It was a point of pride for him to serve what he had cooked, and he'd stand watch over you to make sure you ate every last crumb.

Fernando and I spent the first few days swimming, sunning, reading, and going for walks, or lounging around our simple thatched hut. Unplugged? Let me put it this way: I'd never felt so far from my life in Chicago, ever, and in the best possible way, too. It took me a couple of days to adjust to the pace of beach life, but I was grateful for the opportunity. Fernando wanted this vacation so badly for us both, and I gave myself over to it. At first, I was afraid that turning off my cell phone and letting go of my email would leave me feeling lost. On the contrary, I felt liberated. I felt relieved. At one point, I remember seeing a father and his young son on the beach. The little boy was one of the most beautiful children I had ever seen. "Look at his face!" I said to Fernando. It was a magical thing to watch, this beautiful little kid splashing around in the waves, laughing with his dad.

On the third or fourth day, Fernando started going slightly stir-crazy. The place wasn't nearly as sublime as he remembered. "But I'm so happy just being here with you!" I said. "I have never done anything like this before." Still, I told Fernando that if he was really that eager to leave, why didn't we fly to South America and surprise his nieces and nephews? Fernando said he'd think about it. "So what did you decide?" I asked him an hour or so later. He told me that flying to South America would take two days, and that if I was really, truly happy there—which I kept assuring him I was—then "I guess this is where we're supposed to be."

Once the decision was made to stay, Fernando and I tried to figure out what we could do to help the children we kept seeing. In the end, he was the one who came up with a plan: We could find the twenty poorest families in the area and assemble backpacks for their children. All we needed were the ages and genders of the kids, and we could stuff the backpacks with fabric (for new clothes) and toys and school supplies. We were able to get a list of names, then we went into town for supplies, and for the rest of the day, in the shade of the hotel restaurant, we sat filling up backpacks and securing them with twine. Naturally, he and I argued over the best way to distribute them. I thought the kids should come to the hotel, but Fernando pointed out the kids had grown up nearby and probably never felt welcome at the hotel. In the end, we decided that the next day, December 26, we would invite the families to a place on the beach in front of the hotel and hand out the presents.

Our hut was simple. There was an iron bed with a thin mattress, a desk with a lamp, a chair, and hooks for our clothing. Mud brick walls three-and-a-half-feet high rose up to meet the thatch that covered the roof and the sides of the hut; a little window looked out the back of it.

Both of us were excited about the celebration we had planned for the next morning. It felt good to give something back to a place that was so lovely and hospitable. We fell asleep.

We were still in bed at around 9:00 the next morning when we heard a cracking sound. "What is that?" I asked. As if in response, water started trickling, and then pouring, into the area between the brick and the thatched roof, as if someone were emptying a giant pitcher of water over us. Fernando got out of bed immediately, and grabbed his camera, to make sure it didn't get wet. The children's backpacks we had arranged so neatly on the floor of the hut began swirling around, and the next thing I knew, it was pitch black and I was pinned underneath the bed from the pressure of the water. A few seconds later the roof of our hut was torn off, and Fernando and I were swept out of the hut by strong currents.

When something like this happens, your brain goes to a very primal place. It wants one thing: to survive. You don't ask yourself, Where am I? or Where is Fernando? You don't think, What happened to my wallet? or I'm not wearing anything. What you think about is breathing. I remember telling myself, The only thing I have to concentrate on is the moment I come up for air. I have to take a really deep breath, and then I have to hold on to that breath.

All of a sudden there was light again and I knew it was coming from the sky, which meant I was near the surface, so I shot up and took a deep breath before the water slammed me back under again, sometimes for twenty seconds, sometimes thirty, sometimes for maybe a minute or so, at random intervals. It happened at least half a dozen times. Gulp for air, then back underwater. It felt like being trapped inside a washing machine. I knew that my only job was to preserve my energy so I could rise up, because up meant air. I knew that for reasons I couldn't comprehend water was everywhere. I thought, I am going to die.

Under the water, I remember forcing myself to calm down. And for a moment the currents seemed to have calmed slightly, too. I saw sunlight, and I swam to the surface. By now, I was able to swim, and also to catch my breath. Things were moving past me: babies and barbed wire, cows and cars and men and women and I was trying not to get hit or cut or pulled back under—then suddenly Fernando popped up out of the water, only four feet away from me. I had no idea where we were. I didn't know how far the water had taken us or how close or how far away we were to land. All I could make out was a sea of debris. Then things began coming into focus. I spotted a half-submerged telephone pole. I saw the jut of a rooftop.

By now we were traveling at about 40 miles an hour. The best analogy I can think of is that it was like white-water rafting over rapids, the difference being that these rapids were filled with people and enormous hunks of sharp metal and glass. I had no idea how much time had gone by—five minutes, fifteen minutes, half an hour? I saw that the water was taking us toward that telephone pole and I remember thinking, We're moving so fast, and that pole is coming up so quickly, and if we hit that thing, we could both be knocked out. Just then, a thin mattress from one of the hotel huts floated by and wrapped itself around that pole, so we collided not with the pole but with the mattress. "Hang on, hang on," Fernando called out. I reached over and grabbed hold of his hand around the pole. We hung on to each other, trying to resist the pull of the water. Should we try to climb the pole? I wondered. Then I remembered being taught as a child never to touch wires in water, and realized that if we made it to the top we'd probably be electrocuted. So Fernando and I stayed where we were, clutching each other's hands. I still had no idea what had happened, but the extent of the devastation was becoming clear. People were standing on rooftops, screaming hysterically.

"What was that?" I asked Fernando. "What just happened?" He didn't know, either. "Be strong," he said to me. He said it a second time, and then a third. "Just be strong. Whatever it was," he told me, "it's all over now." A few seconds later, a second wave changed the direction of the water and slammed us both violently off the pole, propelling us backward. Fernando reached for me. I remember him grabbing for the waistband of my underwear, and missing, and then grabbing for my leg, and again missing. I was thrashing wildly, trying to swim, trying to avoid being smashed under the water.

That was the last time I ever saw Fernando, or felt Fernando. I say felt because he and I were always touching in one way or another. Even when we were having dinner at a restaurant, he'd adjust his body so we could be closer to each other. But at that moment I started drowning again, and the primal instinct kicked in, and all I wanted was to breathe. This time I knew there was no way I could survive whatever this thing was . . . but again I saw the sky, and again my lungs clutched for air. I broke through the surface and immediately looked around for Fernando. There was no sign of him. But I convinced myself he was going to be fine. He was a strong swimmer; he was a surfer. He'd grown up in the Brazilian jungle. If anybody could handle himself, it was Fernando.

Again, the water changed direction, and now it was carrying me back over the village. It was then that I spotted a house with a chimney. I remember thinking that if the chimney was still standing, it must be halfway sturdy. I maneuvered myself toward the rear of the house, where I treaded water for a few seconds. I was over what must have been the yard, a palm fence five feet below a rooftop. Somehow I climbed to the top of the fence, where I reached for the lowest roof tiles, boiling-hot from the sun. I knew the only way to save myself was if I could jump from the fence onto that house, climb the roof across the burning tiles, and hold on to the chimney.

The first tiles I clawed at came off in my hands, scalding my fingers. To this day, I don't know how I managed, but I did. I pulled myself up onto the roof, with my legs on fire from the blistering heat of the tiles—and I kept screaming Fernando's name. I knew with absolute certainty that any second he would reappear. I expected to hear him shout back, "Over here, I'm over here," but he didn't. Fifteen feet away, a naked, bleeding stranger sitting on another broken house was sobbing, and at that moment I realized I had blood all over me, too. Another man, floating behind the house, yelled for me to help him. I reached for his hand, but, to my horror, I didn't have the strength. He fell back under the water and I never saw him again.

By now I had a 360-degree view. The water was packed with broken bodies. The sobs and shrieks were almost deafening. A Swedish woman I recognized from the village was up in a tree, and she yelled at me to leave my perch, that another wave was coming. She gestured to an area two hundred feet away, where people were struggling out of the water onto a strip of dry road. I couldn't fathom leaving the security of my rooftop and lowering myself back into the water, but then it dawned on me that Fernando must be over there, where those people were, frantically looking for me. Of course, it made perfect sense that he had gotten himself to a patch of dry land and was trying to find me. I lowered myself down and swam and waded and willed myself across to solid ground.

I kept asking people if anyone had seen a man who looked sort of like me, but no one had. Everyone who survived had made their way to the highest point in the village, a hilltop, where a metal bridge was half suspended in the air. I made my way, too, all the while looking for Fernando. A stranger handed me a pair of shorts, and I put them on. Every place I turned, children were standing alone, crying. I stopped to ask one boy—he was 8 or 9—if he knew where his parents were, and he told me, still crying, that he didn't. "Tell me what they look like," I said, adding that the boy should take a seat in the shade, that he couldn't just wander around the streets by himself. Earlier, I'd met a British couple, both injured and both hysterical, and I knew they were looking for their child. I found them, told them I'd seen a little boy who was searching for his parents, and that he was safe, and that I knew where he was, and that they should stay where they were. Then I got the boy and brought him to his parents. This gave me hope that I would find Fernando, that any second now he would come trudging up the road.

Later that afternoon, I was reunited with Merete, Per's wife from the hotel. Per was dead, she told me. She helped find blankets. We spent that night in a field, having broken into a house that belonged to the local governor, grabbing whatever food and blankets there were, and coping with the alarming rumor that yet another wave was heading to shore. We camped in that field until the first helicopters began showing up with food, followed by more helicopters, which would eventually take us to the military hospital twenty miles away. All the while, I continued searching for Fernando, convincing myself that he had ended up on the other side of a collapsed bridge. I considered swimming across the bay, then realized I was better off staying where I was, and that Fernando would be likelier to find me if all the survivors were in one place.

When dawn came, I hadn't given up hope. But that second day was much harder. Rescuers had begun dragging bodies out of the water in wheelbarrows and stacking them in a schoolhouse across from the field. I had never seen a dead body before, and all I could do was hope and pray one of them was not Fernando. I also managed to call my mother from a cell phone plugged into a car battery, as well as a producer from Oprah. I told her I was surrounded by people who were wounded and children who had lost their parents, and was there anything she could do to help us or publicize what was going on? She immediately mobilized a team of producers to help me and everyone else they could. Like all the people around me, I hadn't eaten for hours—which wasn't a problem for me, as I had no appetite. I must have gone back and forth to the makeshift morgue about forty times, where I lifted up sheets to expose the faces of the men and women who hadn't survived; Fernando wasn't one of them. The rescuers were now piling up the bodies outside, since the schoolhouse had run out of room and was beginning to smell.

That day and the next, rescuers loaded the most injured survivors onto helicopters. At one point, I saw a man I recognized weeping by the side of the road. I realized he was the father of that beautiful little boy Fernando and I had seen playing in the waves. His son was dead. I stood there frozen, watching him weep. It was the first moment I said to myself, That's going to be me.

When it was time to board the helicopter, I resisted. I didn't want to leave without him. But the people around me advised that it would be easier to send out a search party if I were someplace with heat, electricity, working telephones, and Internet service. The next thing I knew, I was in a helicopter that had no doors, gripping a strap as we flew to the military hospital in Ampara, twenty-five minutes away. Next was an eighteen-hour truck ride to the capital, along with a slow- moving line of cars. In Colombo, I stayed for the next week and a half near the American embassy, watching BBC news. A special security team was dispatched by helicopter from Singapore on a mission to scour the area for Fernando. There were a few false sightings. Some people had seen me, and told officials that I was Fernando. I had a working cell phone by now. Every time it would ring, my stomach would turn over, since I didn't know if it meant good news or bad. The only thing I did know was that I wasn't going to leave the country unless I could find Fernando. Instead, I made up various scenarios: Fernando was lost. He had amnesia. He was injured and he couldn't talk and he'd wandered into a nearby village and he had no way to reach me.

But every night, I lay there thinking, This was one more day away from the day of the tsunami, and he still hasn't shown up. Where is he? Where is he? Where is he?

Fernando used to tell everyone that he would never live past the age of 40, and everyone, myself included, hated when he said it. Fernando Bengoechea was 39 years old. His body was never found. He simply disappeared.

I think that's exactly the way he would have wanted it, especially in light of all that I witnessed in the schoolhouse morgue. His brother Marcelo once said to me that the only thing that could ever have taken Fernando off this planet was one of the largest natural disasters in history—it took a tsunami to take Fernando from us. And so I returned to Chicago alone, back to the home he had changed for the better, the place where our lives had joined, where we'd spent so much of our time.

Since December 26, 2004, I have never defined myself by anything other than my ability to survive. I don't think about whether I'm successful, or I'm not successful, famous or not famous, busy or bored. To me, the ultimate question, the only question, is, Can I survive or can't I? That's what matters. I remember once talking to a friend who never seemed able to appreciate the beauty of a moment. She and I had gone to a fantastic destination wedding, and the next day all she kept saying was how she couldn't believe it was over, and that now she'd have to return to her everyday life. I had to remind her that the point of the trip wasn't that it was over, but that it had happened. Which is how I think about the year I had with Fernando.

Coming back to Chicago was one of the hardest things I've ever had to do because it meant acknowledging that Fernando was really, truly gone. I mean, if I were still in Southeast Asia glued to the BBC as the newscasters continued to calculate the death toll, if I were still sleeping on a stranger's floor alongside others who the tsunami had left lost and alone, if I were still fending off friends and family who were begging me to come home, well, that meant I was still inside the experience. Leaving meant the experience was over, that it was the past, that it had become a devastating chapter in my life, and I was now left to face the question of what the future would be like without Fernando.

When I walked back into my apartment for the first time, my mom and dad—who, as I said, had been divorced since I was 2 years old—were sitting on the sofa. They had been together for days, waiting for me to board a plane from Southeast Asia and come home. It was my mother, actually, who told me there was a high risk of airborne illnesses in Sri Lanka and that I should return to the States as soon as I could get a flight. For my health. For my safety. For my sanity.

I spent the first two weeks at home in bed, not showering, not doing much of anything, really, but sleeping when I could and crying constantly and smoking cigarettes nonstop. A doctor came by to check on me, and a psychotherapist showed up at the house every day. I had no appetite, and was weighing in at 150 pounds. Because I was on such a crazy pharmacological cocktail—the doctors at the Sri Lankan hospital prescribed antibiotics, but neglected to explain that they'd also given me Klonopin, a strong tranquilizer—it's no wonder I couldn't sustain much of a conversation with anybody.

One of my greatest comforts at that time was being inside a home that was overflowing with memories. Fernando's imprint and essence and vision—the fact that he'd flipped a vase upside down and set it on the fireplace mantel—held me together when I was coming undone. In the days before we'd left for our trip, we'd had an argument about what I wanted for Christmas.

By now, you've noticed that we were both pretty good at arguing and, like any two people in the process of blending their lives, we did our fair share of it. I told Fernando that the best present I could ever receive would be one of his woven photographs. Fernando had always been inspired by woven crafts. He began cutting up his photos, then weaving the strips back together so that they almost resembled pictorial textiles. He took his work from being beautiful to being something that gave back a little bit more every time you looked at it. He sliced apart a moment, and then remade it on his own terms—more intricate, more fragile, more resonant, and far more unique. At the time I made my request, all twelve of his woven photographs were on exhibit at the Ralph Pucci gallery in Manhattan. Fernando was angry and hurt that I had asked him for one. The truth was, he didn't want to sell any of them, and if he could afford to keep them all, he would have. He wanted to know how I could be so insensitive as to ask him for something he never wanted to part with in the first place? And yet the day before our flight to Asia, Fernando arranged to have not one, but two of them sent to the apartment. And when I got home that first awful night, they were leaning against the wall in the foyer.

I couldn't love those two pieces more. They represent the sacrifice Fernando had made to be with me. He and I shuttled back and forth between New York and Chicago. He always carried the strips of his photos with him in a cardboard tube and worked on them in his spare time. He'd been wanting to give up commercial photography for fine art photography, and those amazing woven photographs symbolized that goal, and his decision to share them with me symbolized the hope he had for our future.

I was deluged with condolences, some a little awkward, some a little misguided, all genuinely well meaning. But one that stands out, that I remember very clearly, was that at some point during those excruciating first weeks, Oprah came to my house. She crawled into bed beside me and listened while I cried. I kept asking, "Why?" It was not a rhetorical question. I needed something to start making sense. She was quiet for a long time, then finally spoke: "I've always believed that when the soul gets what it came to get, it goes."

In that moment, I felt I understood what Fernando had come to get: home. Even though he'd had incredible relationships before we met, his whole life he'd wanted nothing more than a feeling of home, of security. It's what we both wanted and it's what we were fated to give each other.

When you met Fernando, you knew you were among one of the strongest, most purposeful and persistent people you'd ever meet—that he was here to accomplish what he set out to accomplish, and that if you didn't understand that, he had no time for you. He genuinely didn't get what it was like not to have his own way. He set the bar extremely high for people but never any higher than it was set for himself. Because of Fernando, I hold the people I love a little bit longer; I try to listen when I'm too tired to listen; I can't imagine ever worrying, let alone arguing, about taking three weeks off. And not a day goes by when I don't think about him. I know when he would be proud of me, and when he would be disappointed in me. And I also know that the memories I have of making a home and feeling at home with another human being—that is all part of Fernando's legacy.

Did the loss of Fernando make it impossible for me to stay in Chicago? The answer is both yes and no. Stronger than my grief is my instinct for nesting, for creating a space that feels like home. For about a year, I left things in my apartment exactly as they were when Fernando was alive. Then one day I was sitting in my living room, and I found myself wondering, What if those chairs faced the opposite direction? And, What if I moved that metal bookshelf over to that wall—wouldn't that work better in this room? Then I thought, But I can't move them, because this is the way Fernando and I had this room. If I moved things, I would be moving him, and the memories we shared in that space.

In the very next instant, I realized that moving things around and reshuffling interiors and surfaces had been a profound part of our relationship—and that the concept of leaving my apartment as it was, frozen in time like an exhibit, would have made Fernando laugh his ass off, that the best way to honor him was to follow my instincts, to mix it up and continue the experiment, just as I'd done my whole life. My home in Chicago was never about creating a shrine or a permanent collection. Fernando was alive in all the things I surrounded myself with—he still is—and for me to suspend that evolution was in fact the polar opposite of who he was and everything he believed in and everything we'd done together.